The cloud2trees package offers compiled processing routines for generating individual-tree forest inventories directly from aerial point cloud data. Designed to integrate easily into existing silviculture and fire management workflows, the package streamlines complex processing steps that are often fragmented across multiple software tools.

This demonstration provides a broad overview of cloud2trees by walking through the entire process, starting with an overview of point cloud data, progressing the data through the core tree detection and metric extraction pipeline, and concluding with visualization and aggregation of the final outputs. The goal is to illustrate how the package quickly transforms raw 3D data into actionable, attributable, and spatially explicit tree lists ready for further analysis or planning and modeling applications.

Let’s load the libraries we’ll use

Raw Point Cloud Data

We’ll start with a quick overview of aerial point cloud data and its

typical processing in R, independent of the cloud2trees package. Aerial

point cloud data are highly detailed 3D datasets that capture the

forest’s structure. This data is typically acquired via fixed wing

crewed aircraft or uncrewed aerial systems (UAS) equipped with lidar

sensors or high-resolution cameras for Digital Aerial Photogrammetry

(DAP). We will demonstrate basic handling using the widely adopted

lidR package, including initial file loading

(.las/.laz), metadata review, and essential 3D

visualization. See the lidR book by point cloud

processing expert Jean-Romain

Roussel for excellent detail on data processing with this

foundational package.

While lidR provides the necessary foundational tools for

these tasks, cloud2trees steps in to fill the crucial gap by compiling

and automating the more complex, sequential processing steps, including

built-in handling for large extent data that can be challenging for

users scripting a pipeline from scratch.

Let’s load the data for the tutorial which is a small data set that

ships with the lidR package

# the path to a single .las file

las_fpath <- system.file(package = "lidR", "extdata", "MixedConifer.laz")

# load the single file point cloud with lidR selecting only the primary information

las_data <- lidR::readLAS(las_fpath, select = "xyzic")what is this data?

las_data

#> class : LAS (v1.2 format 1)

#> memory : 1.1 Mb

#> extent : 481260, 481350, 3812921, 3813011 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> coord. ref. : NAD83 / UTM zone 12N

#> area : 8072 m²

#> points : 37.7 thousand points

#> type : airborne

#> density : 4.67 points/m²that is very useful information and we can explore the actual data of the point cloud to get more detail

las_data@data %>% dplyr::glimpse()

#> Rows: 37,657

#> Columns: 5

#> $ X <dbl> 481349.5, 481348.7, 481348.7, 481348.6, 481348.6, 48134…

#> $ Y <dbl> 3813011, 3813011, 3813010, 3813009, 3813011, 3813011, 3…

#> $ Z <dbl> 0.07, 0.11, 0.04, 0.02, 0.04, 0.03, 0.10, 0.15, 7.40, 0…

#> $ Intensity <int> 132, 202, 148, 155, 178, 138, 126, 157, 125, 133, 131, …

#> $ Classification <int> 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1…we can explore the X, Y, and Z data further

las_data@data %>% dplyr::select(X,Y,Z) %>% summary()

#> X Y Z

#> Min. :481260 Min. :3812921 Min. : 0.00

#> 1st Qu.:481283 1st Qu.:3812944 1st Qu.: 1.81

#> Median :481305 Median :3812966 Median :14.08

#> Mean :481305 Mean :3812966 Mean :12.01

#> 3rd Qu.:481328 3rd Qu.:3812989 3rd Qu.:18.67

#> Max. :481350 Max. :3813011 Max. :32.07because this is a relatively small data set, we can visualize the 3D data with the points colored by the Z measurement

lidR::plot(

x = las_data

, color = "Z", bg = "white"

, legend = T

, pal = grDevices::heat.colors(55)

, rgl = T

)

rgl::rglwidget()

now that we’ve covered the foundational concepts of point cloud data,

we’re ready to put our cloud2trees pipeline into action using the core

cloud2trees() function to rapidly generate a complete

forest inventory.

Core cloud2trees() Pipeline

The heart of the package is the cloud2trees() function,

which runs the entire Individual Tree Detection (ITD) and attribute

extraction workflow based on settings defined by the user. To illustrate

its immediate simplicity, we will first demonstrate the execution of

this all-in-one pipeline using the default settings, specifying just the

input location of the example point cloud and where we want to save the

results (a temporary directory for this example). While we strongly

recommend that users customize the function parameters to meet their

specific study objectives, this demonstration will illustrate how simply

cloud2trees can process raw point cloud data to produce a spatial forest

inventory tree list as well as intermediate products like the Digital

Terrain Model (DTM) and Canopy Height Model (CHM).

cloud2trees_ans <- cloud2trees::cloud2trees(

input_las_dir = las_fpath

, output_dir = tempdir()

)That single cloud2trees() function call is all that is

needed to produce a spatial forest inventory tree list, DTM, and CHM

from raw point cloud data

Reviewing Outputs

Regardless of the custom parameters selected by the user, upon

successful completion over an area with trees, the

cloud2trees() function will always return a spatial forest

inventory tree list (including core attributes such as height, location,

and crown area as is typical of ITD processing), as well as the

intermediate DTM and CHM rasters. This section focuses on reviewing

these results, visualizing the segmented crowns and tree tops.

Let’s check out what is included in the return from the

cloud2trees() function.

# what is it?

cloud2trees_ans %>% names()

#> [1] "crowns_sf" "treetops_sf" "dtm_rast" "chm_rast"

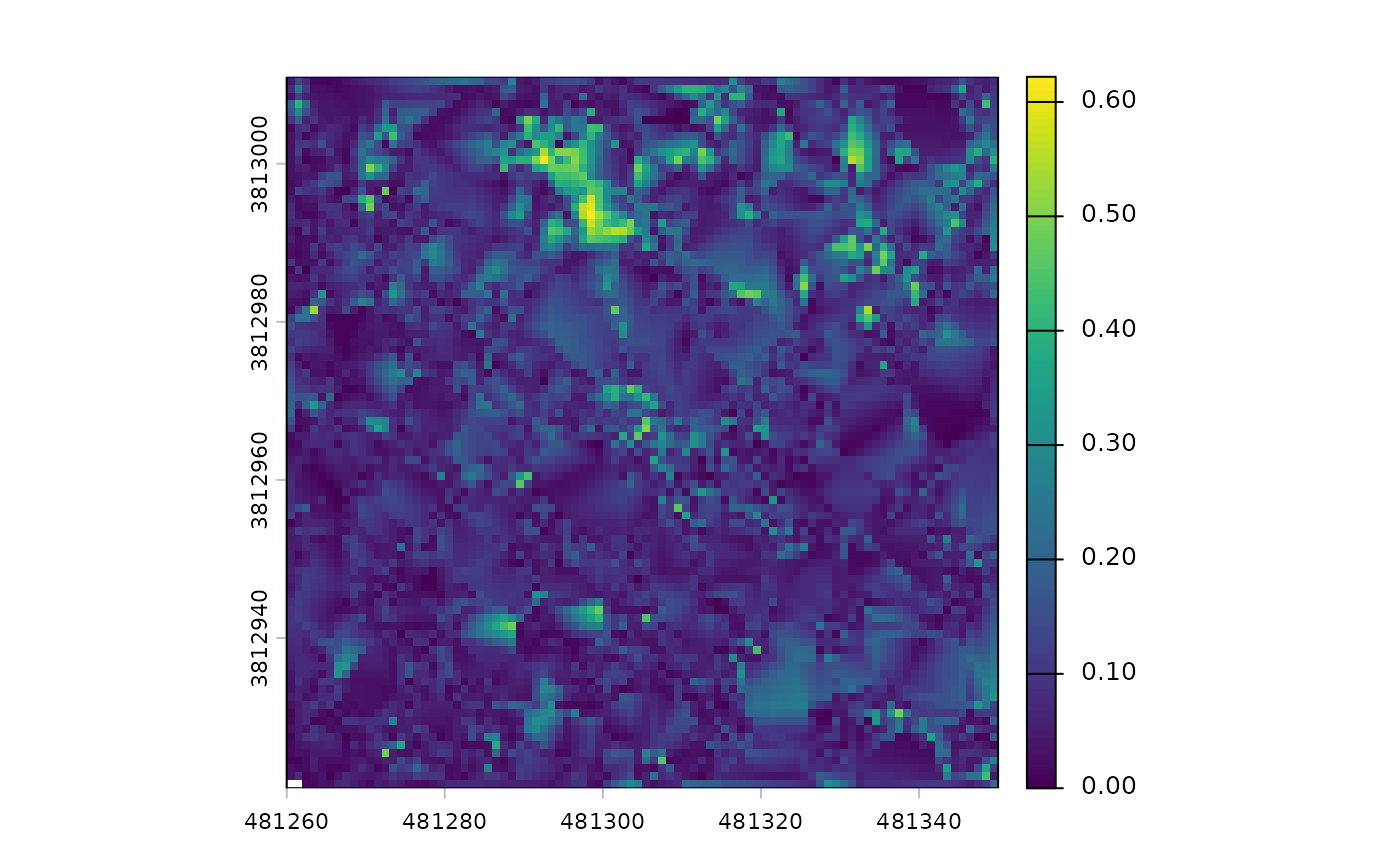

#> [5] "foresttype_rast"There is a digital terrain model (DTM) raster

# there's a DTM

cloud2trees_ans$dtm_rast

#> class : SpatRaster

#> size : 90, 90, 1 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

#> resolution : 1, 1 (x, y)

#> extent : 481260, 481350, 3812921, 3813011 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> coord. ref. : NAD83 / UTM zone 12N (EPSG:26912)

#> source : dtm_1m.tif

#> name : 1_dtm_1m

#> min value : 0.000000

#> max value : 0.622001The DTM was created at the cloud2trees() default 1 m

resolution and that the elevations vary between 0.00 and 0.62 m.

we can plot the DTM using terra::plot()

terra::plot(cloud2trees_ans$dtm_rast)

While the plot shows a fair amount of variation, let’s remember it only represents 0.62 m of vertical relief. If we looked at an area with 60 m of vertical relief, for example, we would not even notice these small fluctuations.

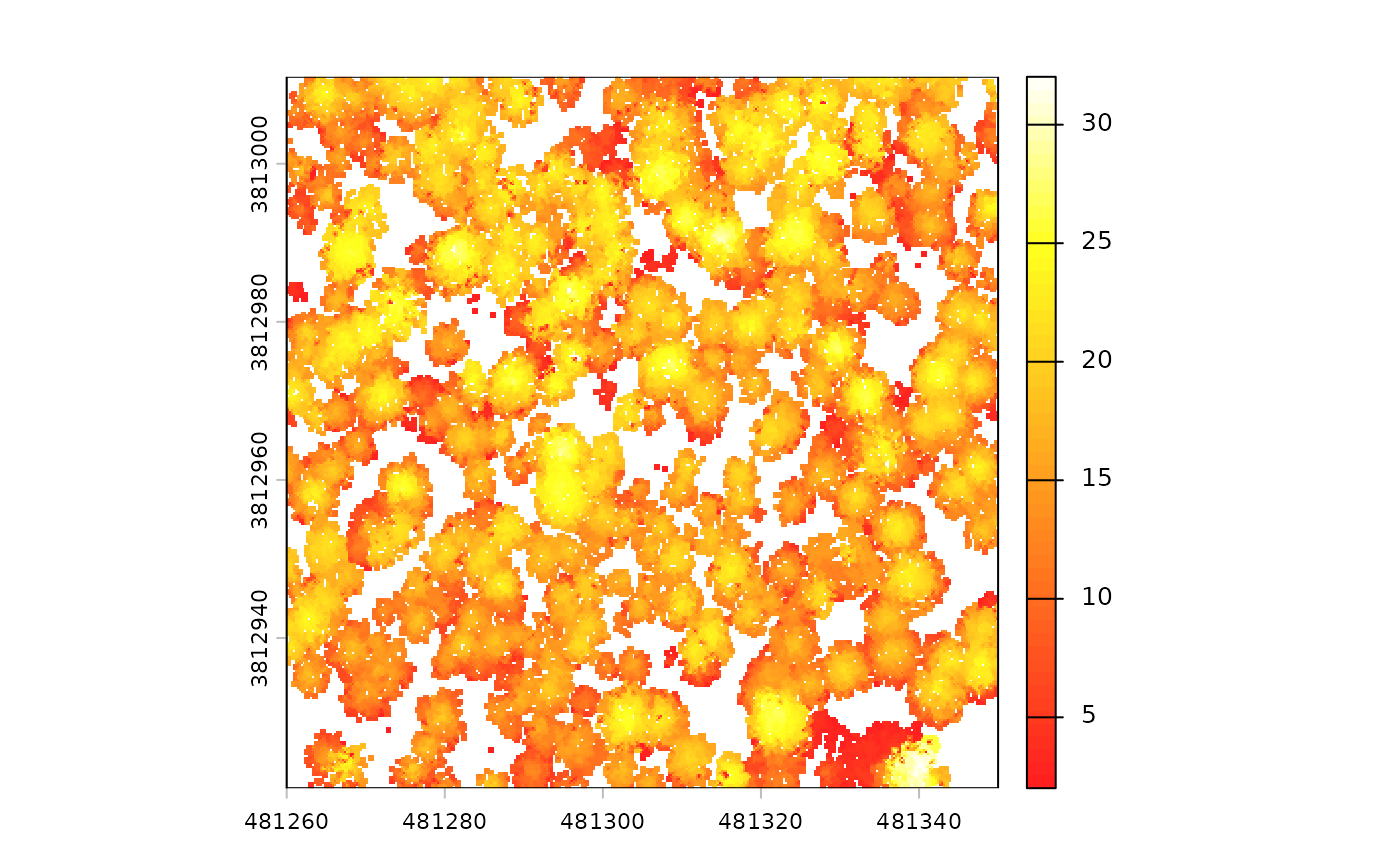

There is a canopy height model (CHM) raster

# there's a CHM

cloud2trees_ans$chm_rast

#> class : SpatRaster

#> size : 360, 360, 1 (nrow, ncol, nlyr)

#> resolution : 0.25, 0.25 (x, y)

#> extent : 481260, 481350, 3812921, 3813011 (xmin, xmax, ymin, ymax)

#> coord. ref. : NAD83 / UTM zone 12N (EPSG:26912)

#> source : chm_0.25m.tif

#> name : chm

#> min value : 2.01

#> max value : 32.02The CHM was created at the cloud2trees() default 0.25 m

resolution and that the elevations vary between 2.01 and 32.02 m.

we can plot the CHM using terra::plot()

terra::plot(cloud2trees_ans$chm_rast, col = grDevices::heat.colors(55, alpha = 0.88))

the treetops_sf object in the return from

cloud2trees() is a spatial data frame representing the

extracted tree tops as individual points

cloud2trees_ans$treetops_sf %>% dplyr::glimpse()

#> Rows: 346

#> Columns: 25

#> $ treeID <chr> "1_481294.4_3813010.9", "2_481312.9_3813010.…

#> $ tree_height_m <dbl> 15.85, 13.44, 22.07, 22.48, 22.92, 24.41, 22…

#> $ crown_area_m2 <dbl> 10.0625, 6.2500, 6.1875, 11.3125, 17.0000, 1…

#> $ fia_est_dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ fia_est_dbh_cm_lower <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ fia_est_dbh_cm_upper <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ is_training_data <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ dbh_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ radius_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ basal_area_m2 <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ basal_area_ft2 <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ ptcld_extracted_dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ ptcld_predicted_dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ tree_cbh_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ is_training_cbh <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ forest_type_group_code <chr> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ forest_type_group <chr> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ hardwood_softwood <chr> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ comp_trees_per_ha <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ comp_relative_tree_height <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ comp_dist_to_nearest_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ max_crown_diam_height_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ is_training_hmd <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ geometry <POINT [m]> POINT (481294.4 3813011), POINT (48131…The tree list contains 346 rows and 25 columns. The 346 rows means

that cloud2trees() detected 346 trees across this 0.81

hectare area. The default use of cloud2trees() provides the

height, crown area, and location (X and Y coordinate) for each of the

trees it identified. However, we also see there are many columns with

NA values and we will explore how cloud2trees can estimate

these attributes in later tutorials.

the crowns_sf object in the return from

cloud2trees() is a spatial data frame representing the

extracted tree crowns as polygons

cloud2trees_ans$crowns_sf %>% dplyr::glimpse()

#> Rows: 346

#> Columns: 27

#> $ treeID <chr> "1_481294.4_3813010.9", "2_481312.9_3813010.…

#> $ tree_height_m <dbl> 15.85, 13.44, 22.07, 22.48, 22.92, 24.41, 22…

#> $ tree_x <dbl> 481294.4, 481312.9, 481325.1, 481333.4, 4813…

#> $ tree_y <dbl> 3813011, 3813011, 3813011, 3813011, 3813011,…

#> $ crown_area_m2 <dbl> 10.0625, 6.2500, 6.1875, 11.3125, 17.0000, 1…

#> $ geometry <GEOMETRY [m]> POLYGON ((481292.5 3813011,..., POL…

#> $ fia_est_dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ fia_est_dbh_cm_lower <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ fia_est_dbh_cm_upper <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ is_training_data <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ dbh_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ radius_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ basal_area_m2 <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ basal_area_ft2 <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ ptcld_extracted_dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ ptcld_predicted_dbh_cm <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ tree_cbh_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ is_training_cbh <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ forest_type_group_code <chr> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ forest_type_group <chr> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ hardwood_softwood <chr> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ comp_trees_per_ha <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ comp_relative_tree_height <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ comp_dist_to_nearest_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ max_crown_diam_height_m <dbl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …

#> $ is_training_hmd <lgl> NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, NA, …Notice that cloud2trees_ans$crowns_sf and

cloud2trees_ans$treetops_sf have the exact same

structure but one is spatial polygons and the other is spatial

points.

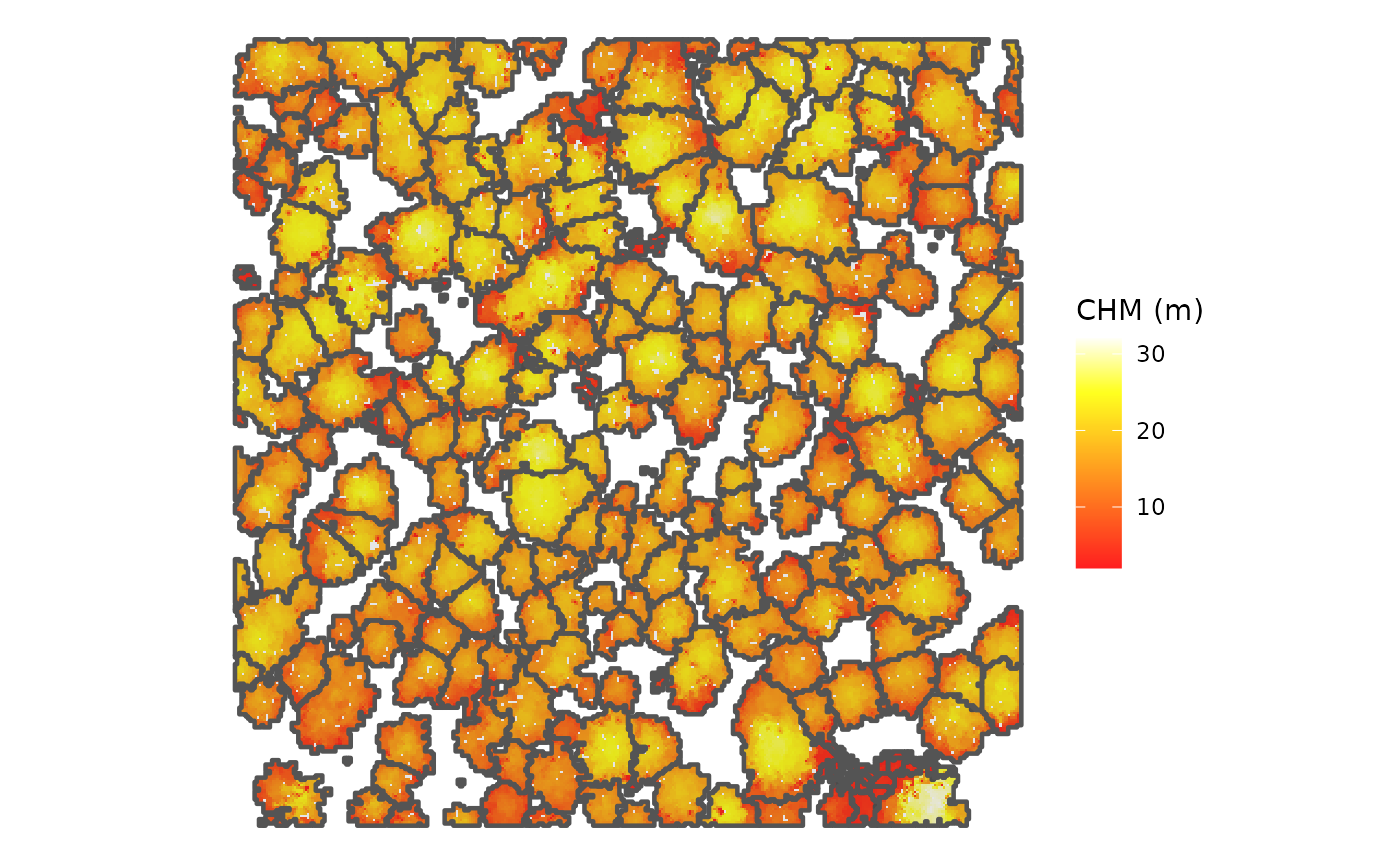

Now let’s create a visual of the individual tree crowns stored in the

crowns_sf object overlaid on the CHM. This time, we’ll plot

using the ggplot2 package

cloud2trees_ans$chm_rast %>%

terra::as.data.frame(xy = T) %>%

dplyr::rename(f = 3) %>%

ggplot2::ggplot() +

ggplot2::geom_tile(

mapping = ggplot2::aes(x = x, y = y, fill = f)

) +

ggplot2::geom_sf(

data = cloud2trees_ans$crowns_sf

, color = "grey33"

, lwd = 0.8

) +

ggplot2::scale_fill_gradientn(colors = grDevices::heat.colors(55, alpha = 0.88)) +

ggplot2::labs(fill = "CHM (m)") +

ggplot2::theme_void()

This figure displays the individual tree crowns that

cloud2trees() identified using its default variable window

function for tree detection (i.e. the ws argument). If you

look closely, you can likely find places where tree crowns are being

over or under divided. In a later tutorial we will look at how the

itd_tuning() function of cloud2trees can be used to

optimize local tree detection given the crown architecture of the forest

being analyzed.

Analyzing Outputs

The ultimate goal of cloud2trees is to provide accurate and spatially

explicit inputs that directly support management decisions. This final

section demonstrates how the output spatial tree list can be immediately

used for forest management and planning. We will showcase examples such

as calculating stand-level metrics (e.g. trees per hectare and mean

stand height), generating height distributions, and identifying

potentially ecologically important trees. This brief overview is meant

to showcase how easily insight can be gained from the

cloud2trees() spatial inventory, improving access to data

and enabling cross-disciplinary integration to spur novel forest

management approaches and enable collaborative action.

Stand-Level Metrics

We’ll pretend our forest stand is the central 4,000 m2 of the point cloud data and create a square polygon to use as our stand boundary

my_stand <-

cloud2trees_ans$treetops_sf %>%

sf::st_union() %>%

sf::st_centroid() %>%

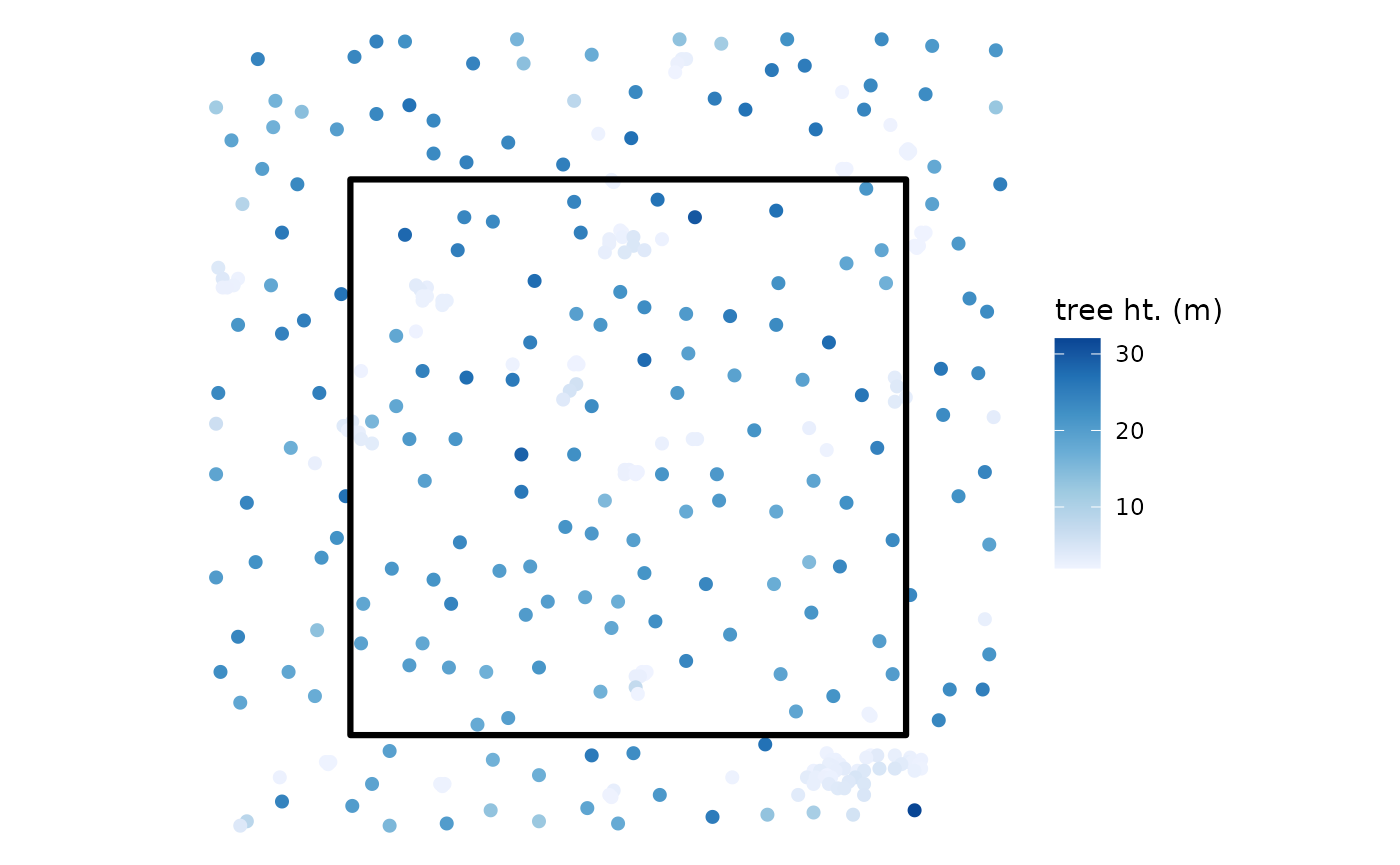

sf::st_buffer(sqrt(4000)/2, endCapStyle = "SQUARE")Let’s look the tree top points identified by

cloud2trees() in relation to the stand boundary. We’ll

color the tree top points by tree height

# what is this?

ggplot2::ggplot() +

# tree tops

ggplot2::geom_sf(

data = cloud2trees_ans$treetops_sf

, mapping = ggplot2::aes(color = tree_height_m)

, size = 1.8

) +

# stand polygon

ggplot2::geom_sf(

data = my_stand

, fill = NA, color = "black", lwd = 1.1

) +

ggplot2::scale_color_distiller(

palette = "Blues", direction = 1, name = "tree ht. (m)"

) +

ggplot2::theme_void()

to get stand-level metrics we can crop our tree list to the stand

boundary and summarize. we’ll do this all in one tidy pipeline but you

can break the pipes (%>%) to see what each step

does.

# first we'll crop the tree list to the stand

treetops_in_stand <- cloud2trees_ans$treetops_sf %>% sf::st_intersection(my_stand)

# summarize

stand_summary <-

treetops_in_stand %>%

sf::st_drop_geometry() %>% # don't need geom now

# summarize

dplyr::summarise(

mean_tree_height_m = mean(tree_height_m)

, n_trees = dplyr::n()

) %>%

# add stand information

dplyr::mutate(

stand_area_m2 = sf::st_area(my_stand) %>% as.numeric()

, stand_area_ha = stand_area_m2/10000

, trees_per_ha = n_trees/stand_area_ha

)

# what is this?

stand_summary

#> # A tibble: 1 × 5

#> mean_tree_height_m n_trees stand_area_m2 stand_area_ha trees_per_ha

#> <dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 13.9 158 4000. 0.400 395.cloud2trees() identified 158 trees in the 0.40 ha stand

resulting in 395.0 trees per hectare (TPH). Based on these 158 trees,

the mean stand height is 13.9 m.

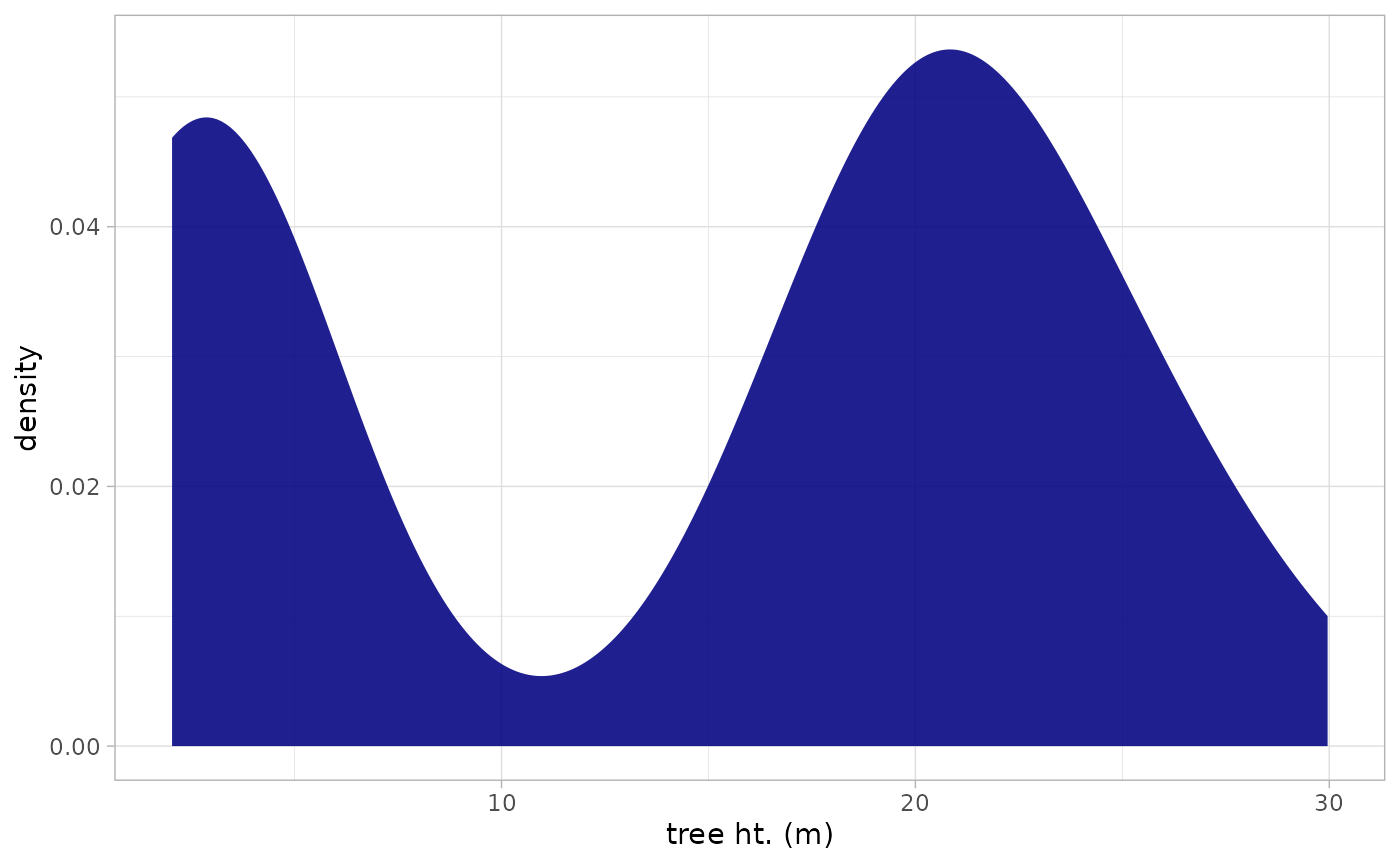

Height Distributions

We’ll continue to look at the trees within our stand to explore the tree height distribution.

A simple density plot of heights can be generated quickly

treetops_in_stand %>%

ggplot2::ggplot() +

ggplot2::geom_density(

ggplot2::aes(x = tree_height_m)

, alpha = 0.88

, fill = "navy", color = NA

) +

ggplot2::labs(x = "tree ht. (m)") +

ggplot2::theme_light()

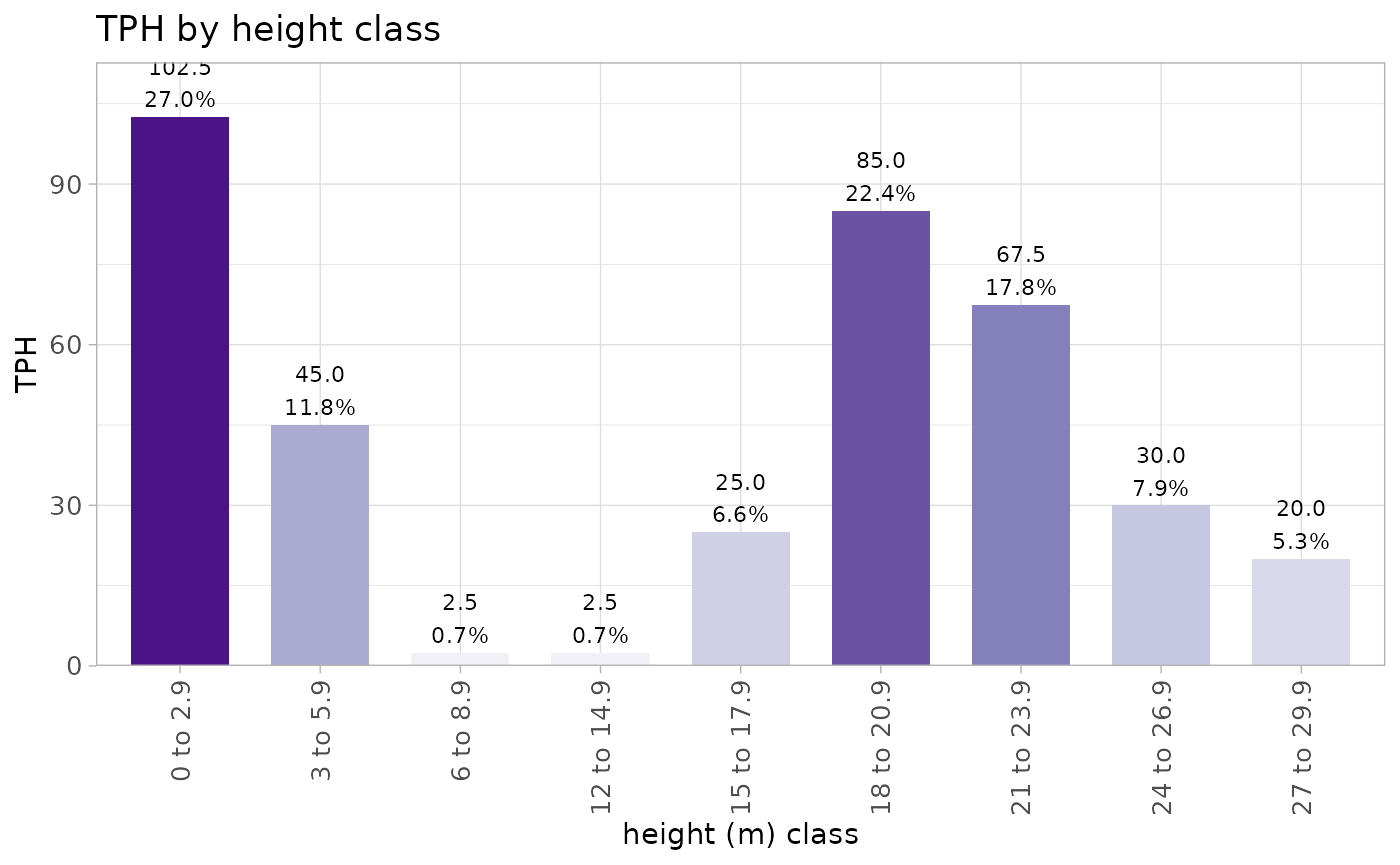

we can also create custom height bins and summarize the trees within

those bins. again, this is one big tidy pipeline but you can break the

pipes (%>%) to see what each step does.

treetops_in_stand %>%

sf::st_drop_geometry() %>%

dplyr::mutate(

height_bin = ggplot2::cut_width(

tree_height_m, width = 3, boundary = 0, closed = "left"

)

) %>%

dplyr::group_by(height_bin) %>%

dplyr::summarise(

n_trees = dplyr::n()

) %>%

dplyr::ungroup() %>%

dplyr::mutate(

stand_area_m2 = sf::st_area(my_stand) %>% as.numeric()

, stand_area_ha = stand_area_m2/10000

, trees_per_ha = n_trees/stand_area_ha

, tot_trees_per_ha = sum(trees_per_ha)

, pct = trees_per_ha/tot_trees_per_ha

, height_bin_lab = paste0(

stringr::word(

height_bin

, 1

, sep = stringr::fixed(",")

) %>% readr::parse_number()

, " to "

, stringr::word(

height_bin

, -1

, sep = stringr::fixed(",")

) %>% readr::parse_number() %>% `-`(0.1)

) %>%

factor() %>%

forcats::fct_reorder(

stringr::word(

height_bin

, 1

, sep = stringr::fixed(",")

) %>% readr::parse_number()

)

) %>%

# plot

ggplot2::ggplot(

mapping = ggplot2::aes(

x = height_bin_lab, y = trees_per_ha

, fill = trees_per_ha

, label = paste0(

scales::comma(trees_per_ha, accuracy = 0.1)

, "\n"

, scales::percent(pct, accuracy = 0.1)

)

)

) +

ggplot2::geom_col(width = 0.7) +

ggplot2::geom_text(color = "black", size = 3, vjust = -0.2) +

ggplot2::scale_fill_distiller(palette = "Purples", direction = 1) +

ggplot2::scale_y_continuous(

labels = scales::comma_format(accuracy = 1)

, expand = ggplot2::expansion(mult = c(0, 0.1))

) +

ggplot2::labs(

x = "height (m) class"

, y = "TPH"

, title = "TPH by height class"

) +

ggplot2::theme_light() +

ggplot2::theme(

legend.position = "none"

, axis.text.y = ggplot2::element_text(size = 10)

, axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 90, size = 10, vjust = 0.5, hjust = 1)

)

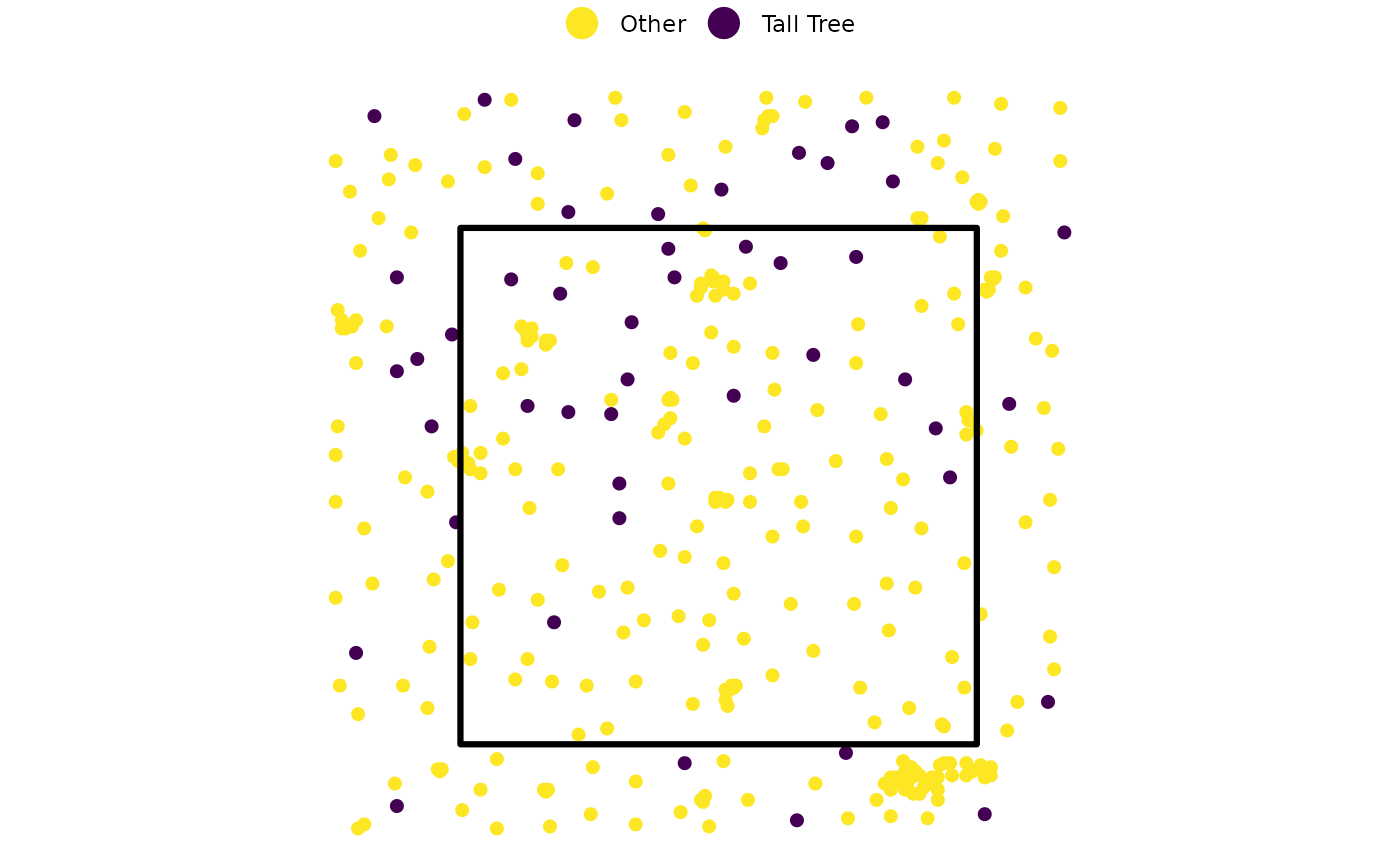

Identify Potentially Ecologically important trees

finally, let’s identify potentially ecologically important trees based on a height threshold of 24 m across the entire extent of the point cloud data

cloud2trees_ans$treetops_sf %>%

dplyr::mutate(

tall_tree = ifelse(tree_height_m>=24,"Tall Tree", "Other")

) %>%

ggplot2::ggplot() +

# tree tops

ggplot2::geom_sf(

mapping = ggplot2::aes(color = tall_tree)

, size = 1.8

) +

# stand polygon

ggplot2::geom_sf(

data = my_stand

, fill = NA, color = "black", lwd = 1.1

) +

ggplot2::scale_color_viridis_d(option = "viridis", direction = -1, name = "") +

ggplot2::theme_void() +

ggplot2::theme(legend.position = "top") +

ggplot2::guides(color = ggplot2::guide_legend(override.aes = list(size = 5)))

since we have the X and Y coordinates of all trees, we can easily load them onto a tablet or GPS device to navigate to those important trees in the field